Reflective Commentary (2025)

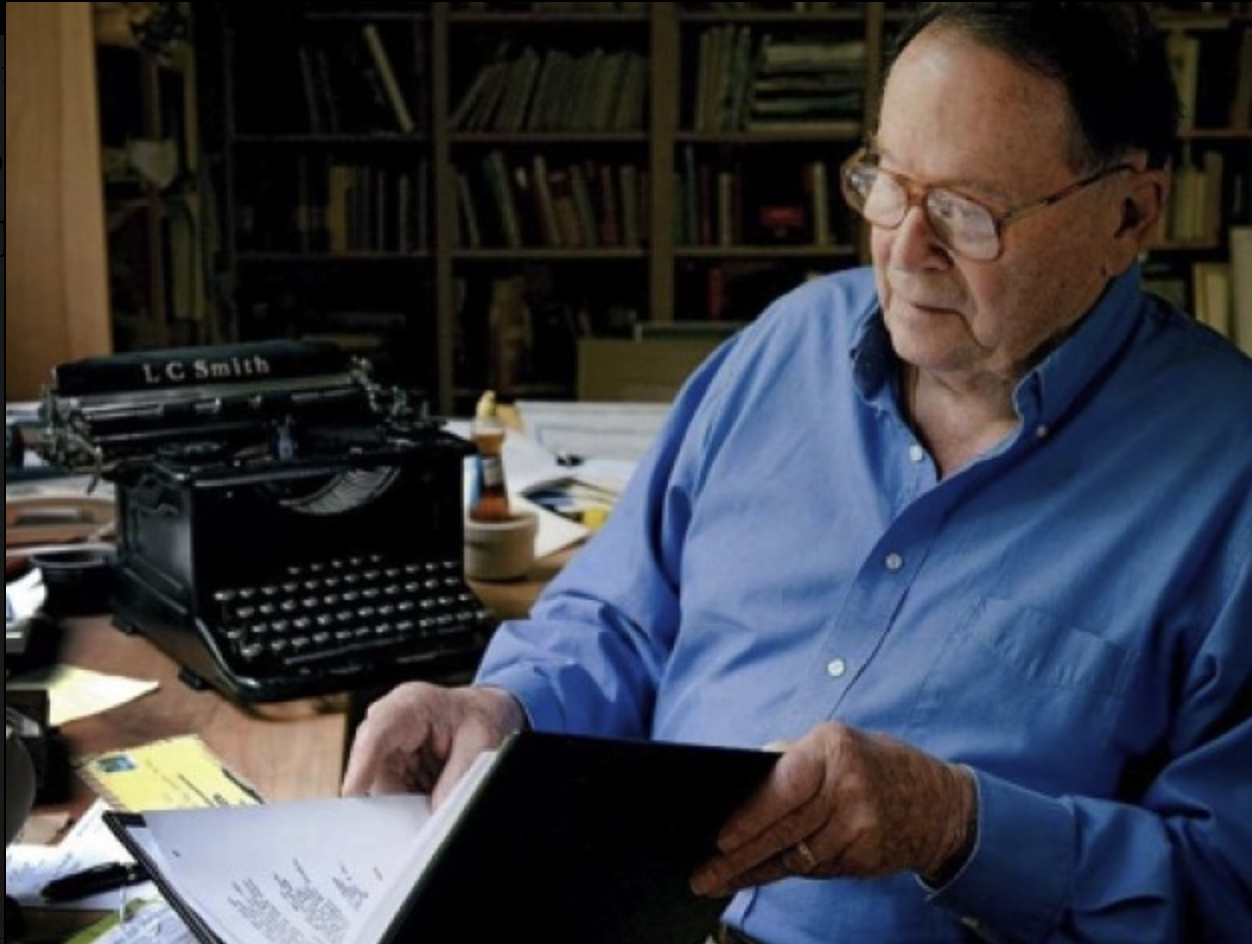

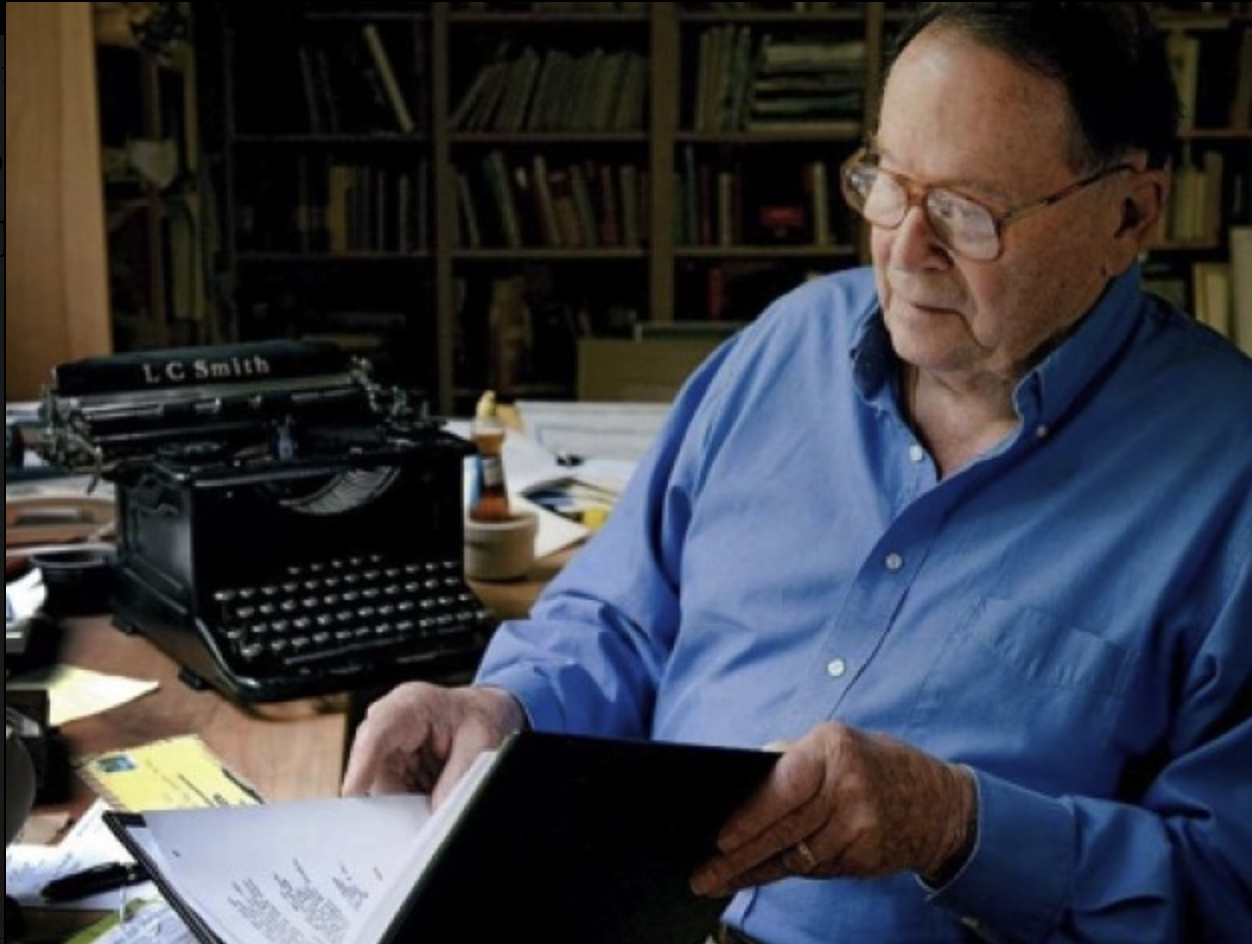

At the time of composing this essay in 2014, Richard Wilbur stood in his ninety-fourth year. I had mistakenly thought that he had already passed, but he was very much alive, a fact Professor Robert Woods gently noted with the hopeful remark, “He is still alive at ninety-four… would that God grants us as many years to enjoy this world before the joys of the one to come.” Only three years later, in 2017, Wilbur would take his leave from this world at the age of ninety-six (born March 1, 1921–died October 14, 2017).

My first encounter with his work came in this doctoral course, and I found his voice invigorating and luminous, as if he had lent me a new lens through which to read the human condition. For that introduction, I remain indebted to Professor Woods, and for the life of Richard Wilbur himself, so wholly lived as a man of letters, I remain profoundly grateful.

Original Essay (2015)

Fifty-five percent of those surveyed in class discussions concluded that Richard Wilbur wrote of the ordinary independent of the extraordinary or of otherworldly concerns. Twelve percent of those surveyed concluded that Wilbur wrote of the extraordinary apart from the ordinary or the physical world. Thirty-three percent of those surveyed concluded that he wrote of the ordinary in concert with the extraordinary. Richard Wilbur, an Episcopalian, wrote of the ordinary in concert with the extraordinary, seeking thereby to engage the deep symbiosis between the physical and the spiritual, the wholeness of man.[1]

The Problem of Worldview Orientation

The problem is exacerbated by conflicting perceptions of the ordinary, which arise as a result of differing worldview orientations. Depending on one’s worldview, all daily interaction within the world is interpreted de facto through the lens of one’s own experience.

Readers inevitably approach Wilbur’s work through these worldview lenses, which produce differing emphases: some discerning the ordinary apart from the extraordinary, others the extraordinary apart from the ordinary, and still others the ordinary in concert with the extraordinary, as reflected in the survey.

Wilbur’s poetic practice, however, appears deliberately to bridge these divides. He resists reducing experience to either a merely secular frame or a purely otherworldly one. Richard Wilbur, an Episcopalian, wrote of the ordinary in concert with the extraordinary, seeking thereby to engage the deep symbiosis between the physical and the spiritual, the wholeness of man.

To think of the ordinary experiences of life as independent of the extraordinary, or of otherworldly matters, is to interpret the world as one-dimensional. This perspective does not allow for a second dimension in which the spiritual might exert its influence upon human beings. For example, a scientist who builds a logical framework based on a model of proof and regards as knowledge only what can be demonstrated through research methodologies is one whose framework is one-dimensional.

To think of the extraordinary experiences of life as independent of the ordinary, or of physical-world matters, is to interpret the world as quasi-dimensional. This perspective becomes a continual task of merely enduring the ordinary while escaping to the netherworld of the mind, the extraordinary, in order to live in the non-physical world. For example, the biblicist who constructs an eschatological framework without scientific evidence and holds as a theory of knowledge only what may be felt or heard from God is one whose framework is quasi-dimensional. Falsus in uno, falsus in omnibus (Latin: “false in one thing, false in all”) is the ancient maxim that reminds us that when one foundation of a framework is false, the credibility of the whole is called into question.

To think of the ordinary experiences of life as in concert with the extraordinary is to engage the symbiosis of the physical–spiritual wholeness of man. This perspective offers a dual dimension (metaphysical) for the spiritual influence on humanity, whose lives are lived in the physical world. For example, the Christian humanist who constructs a “man of letters” framework for the study of the humanities (studia humanitatis), woven into the fabric of a Christian belief system, is working from a dual-dimensional framework.

The Solution of Faith and Imagination

Richard Wilbur was a Christian humanist who openly expressed his belief in the Christian faith.[2] He spoke of his faith journey as he moved through various traditions—Presbyterian, Episcopal, and Baptist. In his time, he emerged as one whose faith was distinctly his own.[3] It is this depth of expression of the ordinary that profoundly reveals the extraordinary. The work of Wilbur may be compared to a well-spoken or well-written parable, which, as the childhood definition has it, is an earthly (ordinary) story with a heavenly (extraordinary) meaning.[4]

From the preceding analysis, several conclusions may be drawn.

Key Conclusions

1. Richard Wilbur wrote of the ordinary while expressing deeply held tenets of his theological framework. However, Wilbur was also a man whose identity was rooted in the ordinary.

2. Richard Wilbur wrote of the ordinary experiences of life as in concert with the spiritual. Thus, his written word engaged the symbiosis of the physical–spiritual wholeness of man.

3. Richard Wilbur articulated a dual-dimensional theology of influence upon the spiritual person whose life was deeply rooted in the physical world.

4. Richard Wilbur was a Christian humanist who built a “man of letters” framework for the study of the humanities (studia humanitatis), woven into the fabric of his Christian belief system, and he was working from a dual-dimensional framework.[5]

The Ordinary as Sacramental

Richard Wilbur’s poetry resists confinement to a single interpretive lens. He neither reduces human experience to the merely material nor does he detach it from the transcendent. Instead, he inhabits the creative tension between the two. His poems anticipate the interpretive challenges of his readers, who approach him with differing worldviews. Yet, he continually offers a vision in which the ordinary and extraordinary meet. What emerges is not a neat resolution but a pattern of integration: the ordinary as sacramental, the extraordinary as enfleshed.

Wilbur’s voice does more than craft images of clarity and wit. It bears witness to a theological imagination capable of grounding the spiritual within the rhythms of daily life. His Christian humanism is neither a retreat from the modern world nor an uncritical embrace of it. Rather, a call to inhabit both dimensions fully. If, as his poems suggest, the spiritual is discovered through the actual, then Wilbur leaves to us a vision of faith lived in concert with creation itself; the poetic that becomes a way of seeing, and perhaps even a way of being.

This essay was completed on April 2, 2015, as part of my doctoral work at Faulkner University. It was written for the course HU 8326: Understanding Humane Letters, under the instruction of Dr. Robert Woods.

Endnotes

[1] “A 1995 Interview with Richard Wilbur,” Image: A Journal of the Arts and Religion no. 12 (1995): 1, accessed April 2, 2015, http://www.english.illinois.edu/maps/poets/s_z/wilbur/imageinterview.htm; Peter Harris, “Forty Years of Richard Wilbur: The Loving Work of an Equilibrist,” Virginia Quarterly Review 66, no. 3 (1990): 413–25.

[2] Richard Wilbur, Collected Poems, 1943–2004 (New York: Harcourt, 2006), 307–8. “Love Calls Us to the Things of This World” expresses a human-oriented faith that promotes the self-achievement of humanity within the framework of Christian axioms (i.e., Christian Humanism). The poem’s scriptural approach is inspected critically, presenting the paradox that the spiritual is found through participation in the physical world of the body.

[3] “A 1995 Interview with Richard Wilbur,” 1.

[4] Ibid., 495. Poem 21 makes reference to the sky or heaven (495). Consider the idea of religious activity being found in the everyday experience of life in “A Plain Song for Comadre” (318). See also “In the Field” (207); “Mind” (314); and “Lamarck Elaborated” (317).

[5] Ibid., 319. Of pagans. Note John Chrysostom (311) and Teresa (154). See also “The Proof” (228); “Matthew VIII, 28ff.” (230); “A Christmas Hymn” (300–301); and “In a Churchyard” (203–4), which appears distinctly Christian Humanist in thought.