Reflective Commentary (2025)

This brief essay, composed in 2015, records my first serious engagement with the post-structuralist theories of Michel Foucault and Jacques Derrida. At that time, my priority was to précis their arguments and to register my own tentative responses as a doctoral student. On re-reading, I recognise the enthusiasm of my engagement, but also the limitations of my critical approach at that stage. My focus lay more in understanding than in interrogating these texts. I was, perhaps, too ready to accept the terms of debate as I found them, and was then less attuned to the historical, cultural, or theoretical contexts in which such concepts might be challenged, applied, or reframed.

When I write ‘as a humanist’, I use the term in its Renaissance sense, specifically as Leonardo Bruni (1370–1444) would have understood it in Florence: a scholar of the studia humanitatis — the literature, rhetoric, history, and moral philosophy of classical antiquity — revived by civic-minded Florentines and by scholars in cities proximate to Florence. This historically particular usage, rooted in civic humanism rather than the later philosophical movement of modern humanism, offered a model for intellectual engagement that was creative, critical, and deeply embedded in civic and textual traditions.

With ten further years of research, teaching, and immersion in contemporary critical debates, my perspective has shifted considerably. I am now more alert to the ways in which foundational theories can both illuminate and obscure. I recognise more fully the plurality of voices, perspectives, and traditions that the canon of Western critical theory has too often marginalised or overlooked. Contextualising the ideas of Foucault and Derrida within specific historical, cultural, and intellectual frameworks has become essential to my scholarly practice. I am also more inclined to question the universalising or totalising tendencies that can sometimes characterise even the most influential theories.

I now understand that critical engagement requires not only mastery of a text’s arguments, but also a readiness to test those arguments against other sources, experiences, and perspectives. The questions I bring to these texts have changed: I am increasingly concerned with how we interpret the classics of antiquity today, through the lens of the Western tradition, theological foundations, and the structural underpinnings of the contemporary world. How does my own position as reader, scholar, and participant in ongoing disciplinary conversations shape my interpretation of these works?

I offer this early work not as a definitive statement, but as a record of intellectual development. It may be of interest to others who, like me, are moving from an initial encounter with critical theory towards a more nuanced and rigorous engagement. Above all, I value the opportunity to make visible the trajectory of scholarly learning, and I hope to model an approach that is both open to new ideas and committed to critical inquiry. By publishing this essay, I wish to encourage readers to value both curiosity and critique, and to see the study of literature and theory as a conversation that never ceases to renew itself — one in which yesterday’s certainties are always open to tomorrow’s questions.

If these reflections prompt further debate or bring other voices into the discussion, I shall be eager to continue the conversation — now with the benefit of hindsight and the many perspectives that have shaped my thinking in the intervening years.

Having offered this reflection on my intellectual journey, I invite the reader to engage with the original essay as it was first written. I now present the essay in its original form, inviting fresh engagement and continued dialogue.

Literary Analysis: Foucault & Derrida (2015)

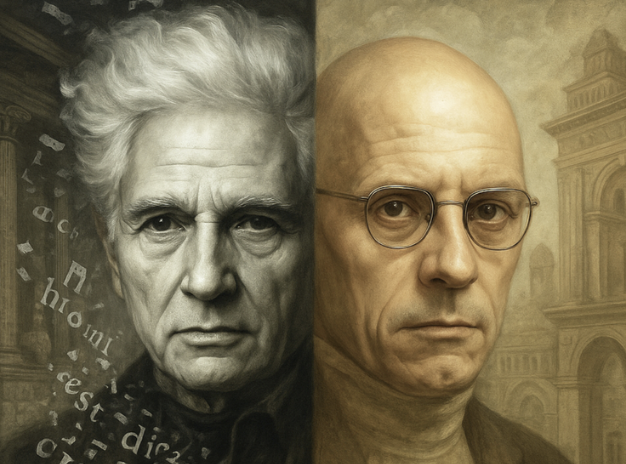

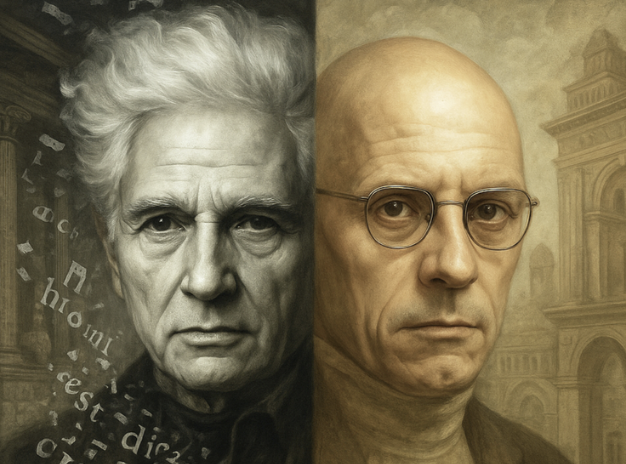

Studies in classical literature such as “What is an Author?” by Michel Foucault and “Structure, Sign and Play” by Jacques Derrida offer principles for the studia humanitatis.[1] The ideas proposed by Michel Foucault (1926–1984) and Jacques Derrida (1930–2004) represent epochs in literary history, forming a partial corpus from which I, as a modern humanist, gain ideological perspective being applied in a post-modern, secular world.[2]

Foucault’s idea of “author” is founded “solely with the relationship between text and author and with the manner in which the text points to this ‘figure’ that, at least in appearance, is outside it and antecedes.”[3] He explores the “fundamental ethical principles of contemporary writing.”[4]

The immanent rule of writing is illustrated by two major themes. One, writing is identified with its own unfolded exteriority. Two, writing is identified by its relationship with death. Foucault states with regard to an unfolding exteriority that “Writing unfolds like a game [jeu] that invariably goes beyond its own rules and transgresses its limits.”[5] As regards death, he references Greek epic and Arabian narratives. Here the author “must assume the role of the dead man in the game of writing.”[6]

We must ask of the author “whether everything that he wrote, said, or left behind is part of his work.”[7] The “notion of writing [écriture]” seems to “transpose the empirical characteristics of the author into a transcendental anonymity.”[8]

Is the person a writer or an author? He concludes, “The author-function is therefore characteristic of the mode of existence, circulation, and functioning of certain discourses within a society.”[9] Foucault asserts:

...the author is not an indefinite source of significations which fill a work; the author does not precede the works, he is a certain functional principle by which, in our culture, one limits, excludes, and chooses; in short, by which one impedes the free circulation, the free manipulation, the free composition, decomposition, and recomposition of fiction.[10]

Foucault works on foundational ideas underlying both author and text. This is displayed in his consideration of whether everything written by an author is to be considered a part of his work as well as his ideas of the author-function: accountability of the author for what is written, variation according to the author’s field of work (science as compared to literary), creation based on patterns rather than spontaneity, and the fact that the word author does not necessarily denote one person as opposed to several persons. He ends his work with transdiscursive authors who work as founders of discursivity.

Derrida writes of “the structurality of structure” (concepts).[11] All structure must have a centre. Never has there been a structure without a centre. The disruption occurred in the midst of the change from one prevailing concept, or centre, to another. To realise there is no centre is to realise there is no structure. The previous structure did not have staying power and there is no new structure. Thus, no centre. Without the centre of philosophy all else becomes discourse (or language). Upon this absence of structure the idea of play emerges. Play is anything that is counter to organisation and coherence in the structure.

My response to these readings is as follows:

Perceived Impact of Foucault & Derrida on My Learning (2015)

Five dimensions derived from the reflections below; 0–5 scale (higher = greater impact).

The radar chart below visualises my perceived impact of Foucault’s What Is an Author? (1969) and Derrida’s Structure, Sign, and Play (1966) across five dimensions drawn from my reflections. Scores are on a 0–5 scale, with higher values indicating greater influence on my thinking in that area.

As reflected in the chart above, Foucault’s work further opened my mind to the dichotomy between the author and his work. Prior to this course [Literary Analysis: Great Ideas, Authors, and Writings taught by Professor Ben Lockerd] (bracketed course information added for clarity), I had not considered the idea of a clear distinction between the author and his work. Foucault’s exploration of what comprises the corpus of an author’s work also deepened my understanding of structure as it pertains to the concept of the author and his output. Derrida, by contrast, informed my grasp of the structurality of structure, challenging all that lies within and without the centre. When I read his work, I am reminded of nihilistic thought, although I have not studied his ideas enough to determine whether this is indeed part of his ontological framework. My response to all the assigned readings this semester has been that of a mind-opening endeavour. I am grateful for the exposure and look forward to revisiting these fine works at a more leisurely pace.

Footnotes

[1] David H. Richter, The Critical Tradition: Classic Texts and Contemporary Trends, 3rd ed. (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's, 2007), 904-914, 914-926.

[2] The listing of dates in this paper is intended to recall the span of history in which these great ideas have not only survived but thrived in the minds of men of letters.

[3] Richter, 904.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid., 904-905.

[6] Ibid., 905.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid., 906.

[9] Ibid., 908. The author-function consists (1) of discourses as “objects of appropriation,” (2) “does not affect all discourses in a universal and constant way,” (3) “does not develop spontaneously as the attribution of a discourse to (4) a real individual.

[10] Ibid., 913.

[11] Ibid., 915.

Bibliography

Derrida, Jacques. “Structure, Sign, and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences.” In The Critical Tradition: Classic Texts and Contemporary Trends, 3rd ed., edited by David H. Richter, 915–926. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2007.

Foucault, Michel. “What Is an Author?” In The Critical Tradition: Classic Texts and Contemporary Trends, 3rd ed., edited by David H. Richter, 904–914. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2007.

Richter, David H., ed. The Critical Tradition: Classic Texts and Contemporary Trends. 3rd ed. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2007.